DREAMLAND

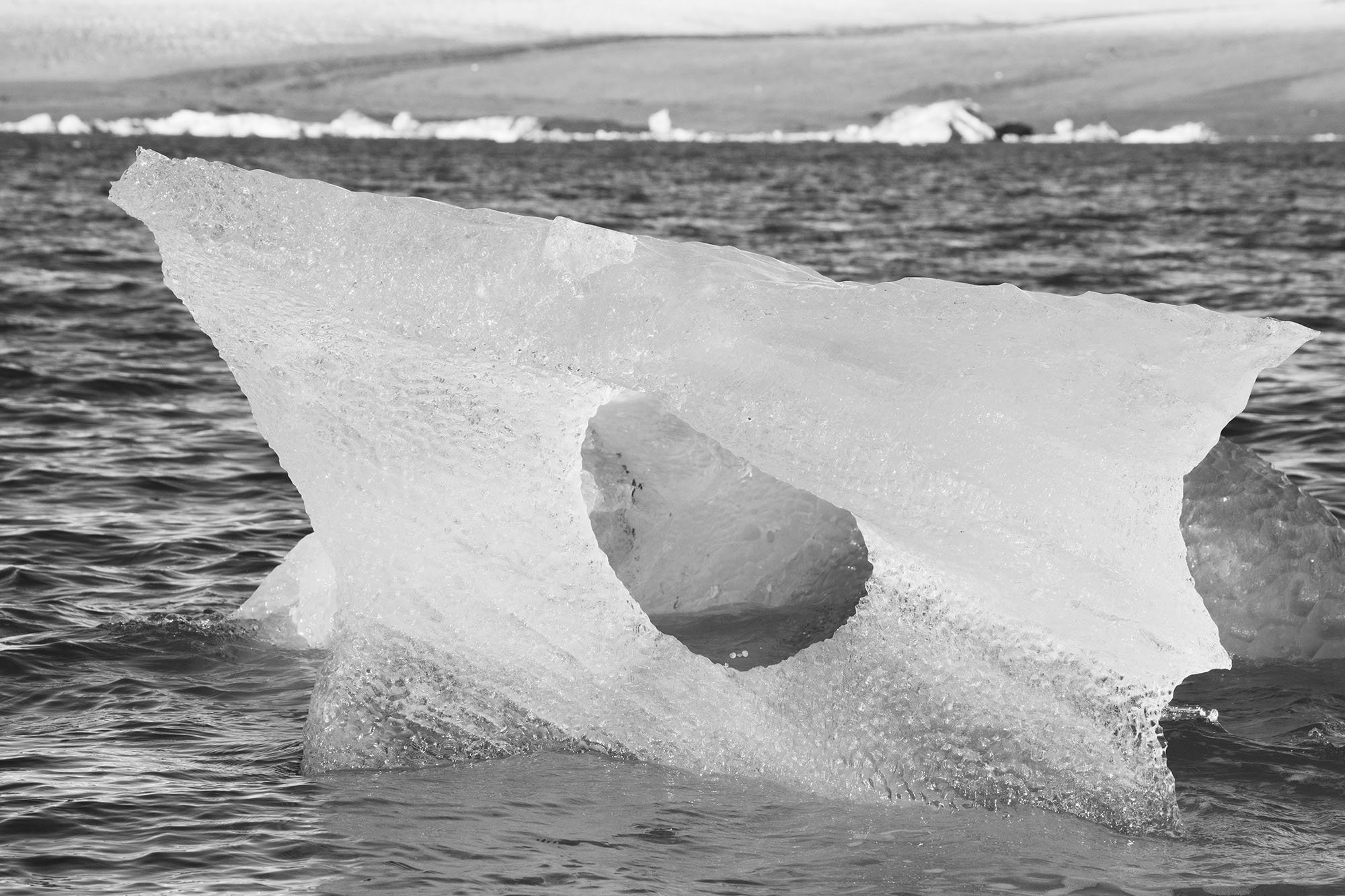

Iceland lies on the mid Atlantic ridge where the North American and Eurasian continental plates are pulling apart and sits on top of the Iceland hotspot which makes it the youngest country on the planet as well and one of the most active volcanic regions in the world. It is a place where one can quite vividly experience the earth’s raw energy pouring forth, it’s life force a reminder of our own. In October 2018 I made my first trip to Iceland and returned again in 2022. On Heimaey island one of the Westman islands named after Irish slaves who escaped there from the Vikings, I have felt the steam from cooling lava at the top of Eldfell volcano which last erupted in 1973 when local people in a heroic effort poured water on the lava flow and saved their fishing harbor, the mainstay of their livelihood. I have watched massive icebergs calve off the tongues of the Vatnajökull glacier, Europe’s largest covering 8% of the country and which is melting at a record pace. That same icesheet melts into some of the world’s most pristine rivers to be captured and channeled towards hydropower stations which fuel the country’s massive and growing aluminum smelter plants owned by some of the biggest multinationals in the world.

In the early to mid 2000s Iceland began to experience an economic boom like never before, fueled by a rapid expansion in tourism numbers and the discovery of Iceland’s extraordinary natural resources by international energy conglomerates eager to exploit it. It’s rapid growth and the challenges which that presented to it’s population and environment mirrored exactly what was happening in my home country of Ireland at the same time.

In 2008 the Icelandic banking system collapsed. Shortly thereafter the same unfolded in Ireland. In both places people were sold an idea of economic prosperity built on the idea that their futures lay in the hands of multinational corporations and global market. Led to believe to believe their salvation lay in the hands of outside forces and the acquisition of material things, it went against everything at the core of both cultures - spirituality and a deep connection to the land rooted in a recognition that our land is sacred, our cultures ancient and our ancestors wise.

In 2008 ‘Dreamland’ a book by Icelandic author Andri Snaer Maganson was released and it had a profound impact on my thoughts about Iceland and the challenges it’s environment and society faced. In it he took a scathing and often tongue in cheek look at the ideas that had been sold to Icelanders about their future in a globalized economy, one in which they would have to sacrifice their greatest natural and human resources. Their great rivers flowing off the glaciers which cover 10% of Iceland would have to be damned and a hydro electric power station built at Gullfoss waterfall, Iceland’s crown jewel, to provide power for American and Canadian aluminium smelter plants in a never ending plan to provide endless energy. People were being encouraged to leave their traditional practices, to forget about being farmers, writers, musicians, stewards of the land all which had set their country apart and had profound influence globally. They were being told they were romantics and that if they were to enjoy a standard of living comparable to the rest of the industrialized world they would have to rewrite their own story and exploit to the maximum their natural resources.

Magnason continues to write “This technological mindset cuts all the deeper because by embracing such a narrow set of values, we are creating our own poverty. Wealth is not to be measured in money but in whether people have the ability to endow their own lives, their environment and culture with meaning and value. Our aesthetic sensibilities, biodiversity and non material riches are closely related to literacy and our appreciation of history, heritage , language and the arts and even human life itself”.

In the final chapter he goes on to say; “Man is free. The machine is there to serve man. And if the machine fails to do this, it is best to switch it off. Over the last few years we have watched as the machine has run out of control….Man tamed nature and then the machine tamed man, until man got a grip on the machine, and on himself.”

My version of Dreamland examines places and ephemeral moments of time that touch a place deep inside that no machine or technology ever could while looking at the real and existential challenges it faces as a nation. The rest of the world seems eager to consume everything Iceland has to offer for many reasons none least because Icelanders seem to have preserved something the rest of us have largely lost. In Dreamland we see at once the sublime, the fragility of earth and human, a world where our two basic instincts, to preserve the land and ensure our security into the future are present.

The difference between Dreamland and most everywhere else is that we walked blindly through our own dreams for the future and took the technocrats at their word without a thought for our Dreamland at home. Which is not to say that in Iceland everything is perfect but here at least there is still a vision that allows us to believe that there is another world where we can harness the earth’s raw and subliminal energy without sleepwalking into our future.